The Disparity in Women’s and Men’s Career Achievements

Women’s and men’s careers have starkly different outcomes. Although women make up 45 percent of entry-level white-collar jobs in the United States, they are only 37 percent of managers, 32 percent of senior managers, 27 percent of vice presidents, 23 percent of senior vice presidents, 17 percent of C-suite executives, and 5 percent of CEOs at S&P 500 companies. The two principal reasons for this gender gap at work are gender bias and women’s own self-limiting beliefs about themselves and their abilities.

What’s Behind the Gender Gap at Work

The New York Times published two opinion pieces with insightful comments about both of these biases. In Why Sexism at the Office Makes Women Love Hillary Clinton, Jill Filipovic argues that the generational split among Democratic women in their support of Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton in 2016 was the result of their different experiences with sexism in the workplace. College-educated women in their early and mid-20s earn 97 cents for every dollar earned by their male colleagues. By the time they are 35, however, women make 15 percent less than their male peers and the pay gap only increases as they grow older. Moreover, the more time women spend in the workplace, the more sexism they experience: managers claiming they want more women but consistently rejecting qualified candidates; senior men being able to work longer hours and take on more responsibilities than their female counterparts because they have stay-at-home spouses who take care of everything else; and women with full-time careers being expected to do significantly more unpaid “domestic” work than their male counterparts. As Filipovic puts it, after working about 10 years, most women realize that “the work world and the world at large remains a place that’s built by men for men.”

Older women identify with Hillary Clinton because they know she has experienced the same sexism they have and has had to fight it every step of her way forward. Young women, on the other hand, support Sanders because, as Hana Schank comments in Salon, they have not “gotten to a place in life where they’ve experienced this kind of chronic, internalized, institutionalized sexism.”

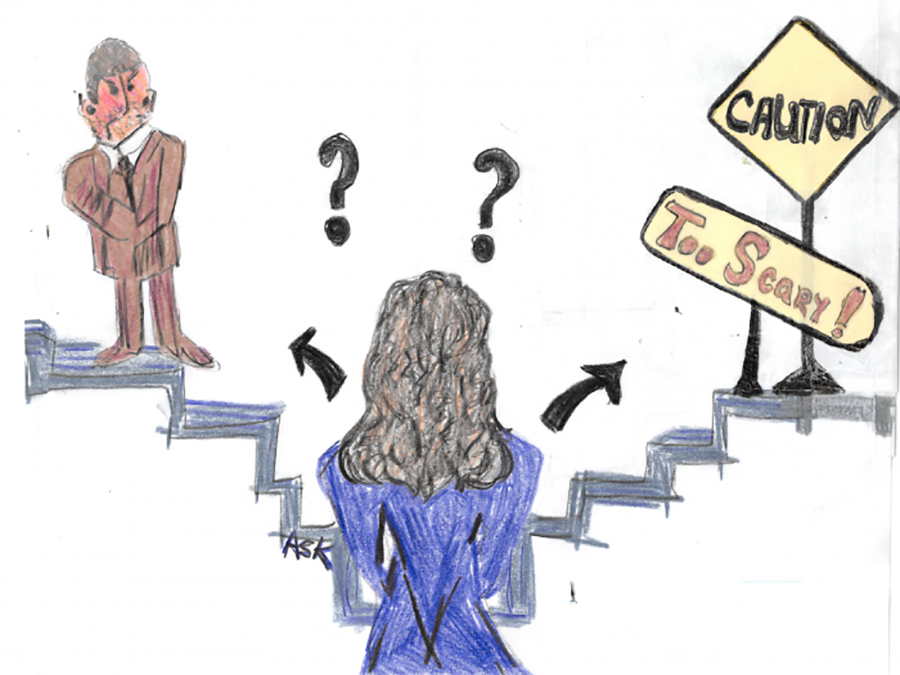

In the second Times article, Why Do We Teach Girls That It’s Cute to be Scared? Caroline Paul, a former San Francisco firefighter, argues that the doubts and uncertainties women so often have about themselves and their abilities are due in large part to their having been taught as girls to be fearful and excessively cautious. One recent study, for example, found that parents are four times more likely to tell girls than boys to be more careful after non-life-threatening mishaps that entail a trip to the emergency room. This over-protectiveness teaches girls to avoid risky physical activities — activities that would help them develop courage and confidence. And when a girl is taught to be hesitant, timid, and fearful, she grows up to be a woman who is deferential, indecisive, and a reluctant leader.

Paul is more pessimistic than we are about a woman’s ability to overcome a childhood of fearfulness and timidity, but her basic point is spot on: In raising girls, “we must chuck the insidious language of fear (Be careful! That’s too scary!) and instead use the same terms we offer boys, of bravery and resilience.” When we caution girls away from dangerous activities “we are not protecting them. We are failing to prepare them for life.”

How Women Can Challenge the Gender Gap

Filipovic and Paul each focus on a different reason for the gender gap at work. The sexism Filipovic discusses is created and driven by gender stereotypes. Because they are women, women are viewed as less competent, ambitious, and competitive than men. Because they are mothers, working moms are viewed as less committed and capable than women without children and all men. And because they are acting contrary to traditional female stereotypes, women who behave with authority, decisiveness and strength — agentic behavior — are viewed as socially insensitive, unpleasant and “unfeminine.”

The inculcation of fearfulness in childhood that Paul discusses often results in women who are hesitant to take on projects outside their comfort zones — precisely the projects that could provide them with the experience, knowledge, and confidence to move up in their organizations.

The gender bias in the workplace Filipovic identifies is pervasive and inescapable. With courage and grit, however — and the right gender communication techniques — women can combat and overcome this bias. But they will never be able to do this if they have self-limiting biases about themselves and their abilities of the sort Paul discusses. Risk-taking is essential for career success — and failure is not an indication of a lack of ability but an occasion to learn and grow. A woman can overcome childhood fearfulness, but it requires persistence and resilience.