Looking for a Cure for Bias?

Do you struggle with whether or not to tell someone a piece of food is stuck to a tooth or their chin? If performing this helpful act makes you uncomfortable, how likely are you to point out someone’s bias as many suggest that we do?

Mixed reactions greet those courageous enough to call out bias. Some emotionally intelligent individuals accept the feedback and work to be more impartial. Others, however, when advised of a bias, react defensively; deeply offended in the same way they would be if told they were hateful, fat, or stupid. Backlash happens because it’s natural to believe ourselves fair and open-minded. Having been on the receiving end of an unpleasant reaction, how many of us are going to wade into those waters again?

Another bit of common bias prevention advice is that we monitor our own biases. Good counsel, but doing so can be tricky. A bias is a conscious or unconscious interpretative preference or inclination that steers us toward one-sided partiality. Sometimes we’re aware of our preferences. Others times we’re not. When we make unconscious pairings between ideas, concepts, individuals, items, places, perspectives, etc. as we add them to our memory, we’re doing what author Malcolm Gladwell calls thinking without thinking. Against the unthinking backdrop, how feasible is it for us to consciously monitor our unconscious thoughts?

As we’re seeing, managing bias is difficult. However, it isn’t impossible.

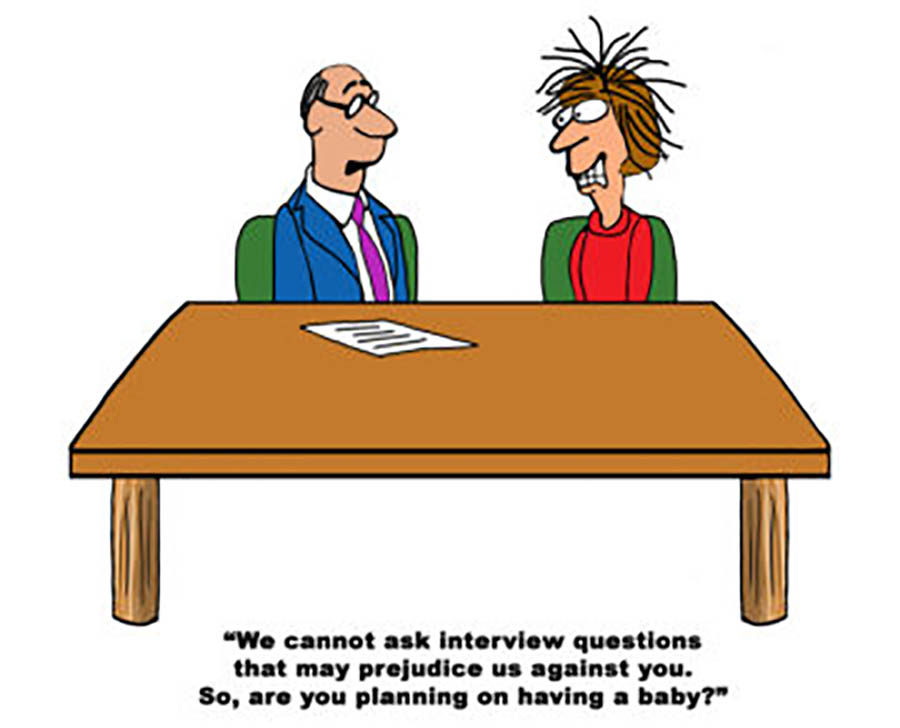

A bias, in and of itself, is merely a mental preference, not always an indicator of bigotry or hatred. That preference becomes prejudicial or discriminatory only when we take detrimental action based on our one-sided inclinations. Unfair treatment can be prevented if we create personal and organizational fail-safes that prompt us to see with new eyes, thus protecting others and ourselves when we act without reviewing our thinking.

Let’s explore some potential bias mitigation fail-safes and why they’re needed.

In the workplace, humans build the systems and processes that are used and create the norms that govern behavior. The result is that implicit bias, and its cousin institutional bias, play an embedded and often unrecognized role in hiring and promotion practices, performance evaluations, succession planning, and other decision-making processes—all happening despite the presence of well-intentioned “we aren’t biased and don’t discriminate” policies.

We’re all biased. My preference for chocolate ice cream is a bias. It isn’t a problem unless I question the abilities or character of those who don’t share my partiality. The icky downsides of bias appear when:

- We pair up task and gender assumptions—like when we think male when we think leadership.

- We ignore individual attributes and view people only as a group—common notions such as all Asians are good with math or all old maids like cats.

- We’re faced with incomplete information—like assuming the woman who has children can’t accept the promotion that requires travel.

- We solve a social problem like diversity with numbers and tokenism—like believing the twelve-member senior team is diverse because there’s one woman.

- We’re in a hurry and go with our default thinking.

All of these factors are manageable. Professor Peter Elbow offers a safe and practical way to manage them, “Our best hope for finding invisible flaws in what we can’t see in our own thinking is to enter into different ideas or points of view—ideas that carry different assumptions. Only after we’ve managed to inhabit a different way of thinking will our currently invisible assumptions become visible to us.” Let’s examine a few ways we can put his advice to work.

Many bias training programs, however well-meaning, give incomplete information. A training program focused only on bias awareness can actually make bias worse. The messaging that everyone has biases unintentionally legitimizes prejudice, i.e., everyone is doing it, so my doing it, too, isn’t a problem. Effective and thorough bias training programs fulfill several objectives: they educate, create awareness, and communicate that people need to correct for bias since the company and its employees value fair treatment, equal access, and respect.

The practice of ignoring individual attributes and relying on stereotypes can be moderated by assigning alternating individuals the role of devil’s advocate. Those in this role are responsible for tactfully taking a contrarian view in which they point out errors and omissions in facts, interpretative judgments, the presence of biased thinking and stereotypes, etc. Having a devil’s advocate allows one-sided groupthink to be safely challenged without attack or assigning blame.

The pairing up of task and gender assumptions can be sussed out through blind reviews of plans, proposals, hiring and promotion decisions, etc. in which the name(s) of the idea source or candidate is withheld. The likelihood of making decisions based on sex, gender, age, race, and even personality conflicts is eliminated.

Given that biases are often unconscious and institutionally embedded, building and using nonjudgmental, creative, and empathetic fail-safes to mitigate their impacts puts us in the position where we can provide fair treatment, equal access, and respect for all.

Ready to get started?

—

Jane Perdue, Executive Director and founder of the consulting firm The Jane Group and a Fortune 500 company executive for 15 years, consults, speaks, advocates, and writes about leadership, power, and positioning women’s issues as business issues. She has been featured as a leadership and women-in-business expert in newspapers, magazines, radio, and television. She speaks at national and regional conferences and has co-authored two books about leadership. Jane loves chocolate, TED talks, kindness, paradox, and shoes.